Spontaneous Chronic Corneal Epithelial Defects (SCCEDs)

By Rachel Mathes, DVM, MS, DACVO

Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects or so called “SCCED” lesions are superficial corneal ulcers that occur in middle-aged, usually large breed dogs, although they may be seen in any breed (1). SCCED lesions, also known as non-healing ulcers, “indolent” ulcers and “Boxer” ulcers, have a typical clinical presentation and appear as large superficial corneal ulcers with marked epithelial lipping (1,2).The epithelial lip may be seen using focal illumination (e.g. Finhoff transilluminator) or may be highlighted with fluorescein staining with the stain noted to migrate under the epithelial lip. Once the loose epithelium is debrided, the ulcer is often much larger than what is seen prior to debridement. These ulcers may also be associated with dramatic secondary corneal vascularization and granulation tissue.

Although the exact cause of SCCEDs is not known, this defect is thought to be an abnormality in the adhesive mechanism of the corneal epithelium to the stroma (1,3). Upregulation of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 2 and 9 is not a characteristic of these lesions (4). An acellular, hyaline membrane is found on histopathology in the ulcer bed and is thought to be contributory in preventing normal epithelial adhesion during the healing process (1). Although uncommonly these ulcers may become secondarily infected and prophylactic antibiotic therapy is warranted, bacterial infections are not causative in these cases. Aggressive antibiotic therapy or periodic switching of topical antibiotics will have no effect on these ulcers and may potentiate resistant bacterial infection.

Treatment for SCCEDs is aimed at creating very superficial stromal abrasion mechanically. Occasionally, debridement of the ulcer with a sterile cotton tipped swab will effect healing. More commonly, however, a more aggressive treatment such as a diamond burr keratectomy or grid keratotomy is required to initiate healing (3.5). Grid keratotomies cause more stromal damage and resultant astigmatism than diamond burr keratectomies (5). Recent studies have shown a very high success rate after diamond burr keratectomy with 70% healed at 1 week and 92.5% healed at 2 weeks (3). Topical chondroitin sulfate may also be beneficial in promoting epithelial adhesion and may decrease surface shearing forces (5).

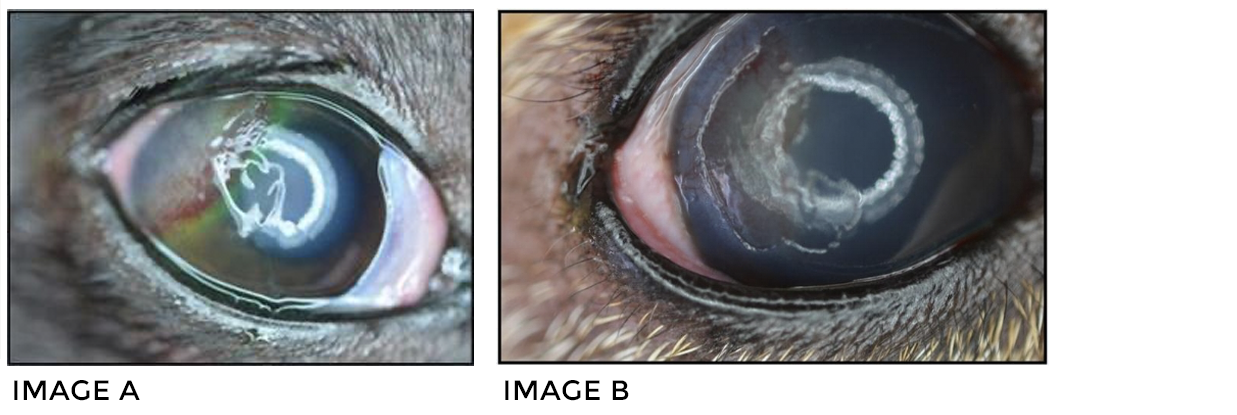

Typical SCCED lesions are pictured. Not the prominent irregular, raised corneal granulation tissue and epithelial margin (arrow) with fluorescein stain migrating under the epithelial lip (A). A well demarcated focally extensive superficial ulcer is present with an epithelial margin after debridement (B).

REFERENCES

- Bentley, et al. Spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs: a review. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005: 41; 158-65.

- Ledbetter, et al. Efficacy of two chondroitin sulfate ophthalmic solutions in the therapy of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects and ulcerative keratitis associated with bullous keratopathy in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol. 2006: 2; 77-87.

- Gosling, et al. Management of spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects in dogs with diamond burr debridement and placement of a bandage contact lens. Vet Ophthalmol. 23 April 2012, online early view.

- Carter, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 and 9 in experimentally wounded canine corneas and spontaneous chronic corneal epithelial defects. Cornea. 2007: 10; 1213-1219.

- Da Silva, et al. Histologic evaluation of the immediate effects of diamond burr debridement in experimental superficial corneal wounds in dogs. Vet Ophthalmol. 2011: 4; 285-291.